eLua architecture overview

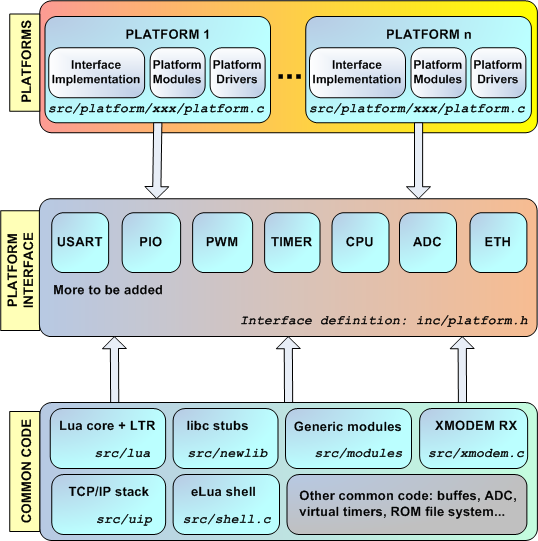

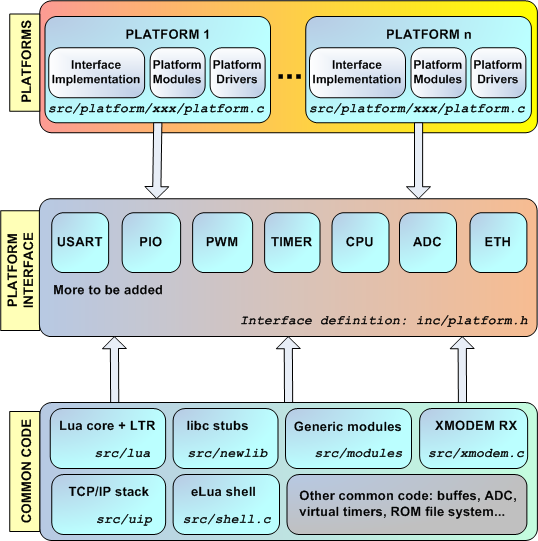

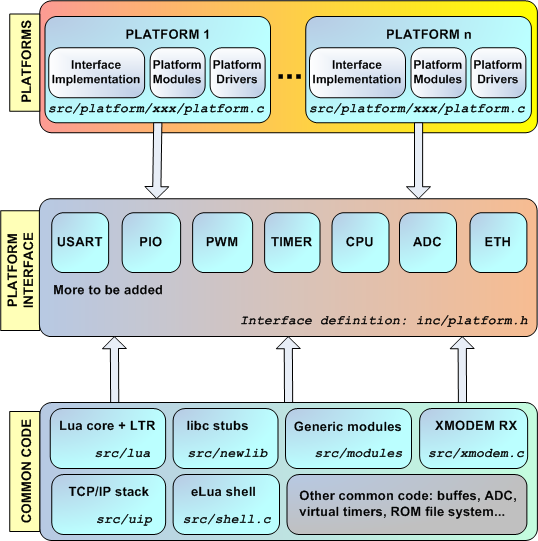

The overall logical structure of eLua is shown in the image below:

eLua uses the notion of platform to denote a group of CPUs that share the same core structure, although their specific silicon

implementation might differ in terms of intergrated peripherals, internal memory and other such attributes. An eLua port implements one or

more CPUs from a given platform. For example, the lm3s port of eLua runs on LM3S8962, LM3S6965 and LM3S6918 CPUs, all of them part of the

lm3s platform. Refer to the status page for a full list of platforms and CPUs on which eLua runs.

As can be seen from this image, eLua tries to be as portable as possible between different platforms by using a few simple design

rules:

- all code that is platform-independent is common code and it should be written in ANSI C as much as possible, this makes it highly portable

among different architectures and compilers, just like Lua itself.

- all the code that can't possibly be generic (mostly peripheral and CPU specific code) must still be made as portable as possible by using a common

interface that must be implemented by all platforms on which eLua runs. This interface is called platform interface and is discussed in

detail here (but please see also "The platform interface"

paragraph in this document).

- all platforms (and their peripherals) are not created equal and vary greatly in capabilities. As already mentioned, the platform interface tries

to group only common attributes of different platforms. If one needs to access the specific functionality on a given platform (like the loopback support

mentioned before) it can do so by using a platform module. These are of course platform specific, and their goal is to fill the gap between the

platform interface and the full set of features provided by a platform.

Common (generic) code

The following gives an incomplete set of items that can be classified as common code:

- the Lua code itself (obviously) plus the LTR patch.

- all the components in eLua (like the ROM file system, the XMODEM receive code, the eLua shell, the TCP/IP stack and others).

- all the generic modules, which are Lua modules used to expose the functionality of the platform to Lua.

- generic peripheral support code, like the ADC support code (src/common/elua_adc.c) that is independent of the actual ADC

hardware.

- libc code (for example allocators and Newlib stubs).

This should give you a pretty good idea about what "common code" means in this context. Note that the generic code layer should be as "greedy" as

possible; that is, it should absorb as much common code as possible. For example:

- if you want to add a new file system to eLua, this should definitely be generic code. It's likely that this kind of code will have

dependencies related to the physical medium on which this file system resides. If you're lucky, you can solve these dependencies using only the functions

defined in the platform interface (this would make sense if you're using a SD card controlled over SPI, since the

platform interface already has a SPI layer). If not, you should group the platform specific functions in a separate interface that will be implemented by

all platform that want to use your new file system. This gives the code maximum portability.

- if you want to add a driver for a specific ADC chip that works over SPI, the same observations apply: write it as common code as much as you can,

and use the platform interface for the specific SPI functions you need.

When designing and implementing a new component, keep in mind other eLua design goal: flexibility. The user should be able to

select which components are part of its eLua binary image (as described here), and the implementation should take

this into consideration. The same thing holds for the generic modules: the user must have a way to choose the set of modules he needs.

For maximum portability, make your code work in a variety of scenarios if possible (and if that makes sense from a practical point of view).

Take for example the code for stdio/stdout/stderr handling (src/newlib/genstd.c): it acknowledges the fact that a terminal can be implemented

over a large variety of physical transports (RS-232 for PC, SPI for a separate LCD/keyboard board, a radio link and so on) so it uses pointers for its

send/receive functions (see this link for more details). The impact on speed and resource consumption is minimum, but

it matters a lot in the portability department.

Platform interface

Used properly, the platform interface allows writing extremely portable code over a large variety of different platforms, both from C and from Lua.

An important property of the platform interface is that it tries to group only common attributes of different platforms (as much as possible).

For example, if a platform supported by eLua has an UART that can work in loopback mode, but the others don't, loopback support won't be included

in the platform interface.

A special emphasis on the platform interface usage: remember to use it not only for Lua, but also for C. The platform interface is mainly used by the

generic modules to allow Lua code to access platform peripherals, but this isn't its only use. It can (and it should) also be used by C code that wants

to implement a generic module and neeeds access to peripherals. An example was given in the previous section: implementing a new file system.

The platform interface definition is always in the inc/platform.h header file. For a full description of its functions, check

the platform interface documentation.

Platforms and ports

All the platforms that run eLua (and that implement the platform interface) are implemened in this conceptual layer. A port is a full

eLua implementation on a given platform. The two terms can generally be used interchangeably.

A port can (and generally will) contain specific peripheral drivers, many times taken directly from the platform's CPU support

package. These drivers are used to implement the platform interface. Note that:

- a port isn't required to implement all the platform interface functions, just the ones it needs. As explained

here, the user must have full control over what's getting built into this eLua image. If you don't need the SPI

module, for example, you don't need to implement its platform interface.

- a part of the platform interface is implemented (at least partially) in a file that is common for all the platforms (src/common.c). It

eases the implmentation of some modules (such as the timer module) and also implements common features that are tied to the platform interface,

but have a common behaviour on all platforms (for example virtual timers, see ##here for details). You probably won't need to modify

if you're writing platform specific code, but it's best to keep in mind what it does.

A platform implementation might also contain one or more platform dependent modules. As already exaplained, their purpose is to allow Lua

to use the full potential of the platform peripherals, not only the functionality covered by the platform interface, as well as functionality that

is so specific to the platform that it's not even covered by the platform interface. By convention, all the platform dependent modules should be

grouped inside a single module that has the same name as the platform itself. If the platform dependent module augments the functionality of a

module already found in the platform interface, it should have the same name, otherwise it should be given a different, but meaningful name. For example:

- if implementing new functionality on the UART module of the LM3S platform, the corresponding module should be called lm3s.uart.

- if implementing a peripheral driver that for some reason should be specific to the platform on the LPC2888 platform, for example its dual audio

DAC, give it a meaningful name, for example lpc288x.audiodac.

Structure of a port

All the code for platform name (including peripheral drivers) must reside in a directory called src/platform/<name> (for example

src/platform/lm3s for the lm3s platform). Each such platform-specific subdirectory must contain at least these files:

- type.h: this defines the "specific data types", which are integer types with a specific size (see coding style

for details. An example from the i386 platform:

typedef unsigned char u8;

typedef signed char s8;

typedef unsigned short u16;

typedef signed short s16;

typedef unsigned long u32;

typedef signed long s32;

typedef unsigned long long u64;

typedef signed long long s64;

- conf.py: this is the platform specific build configuration file, used by the build system for a number of purposes:

- to get the list of platform-specific files that will be compiled in the eLua image. They are exported in the specific_files string,

separated by spaces, and must be prepended with the relative path to the platform subdirectory. An example from the i386 platform:

specific_files = "boot.s common.c descriptor_tables.c gdt.s interrupt.s isr.c kb.c monitor.c timer.c platform.c"

# Prepend with path

specific_files = " ".join( [ "src/platform/%s/%s" % ( platform, f ) for f in specific_files.split() ] )

- to get the full command lines of the different toolchain utilities (linker, assembler, compiler) used to compile eLua. They must be declared

inside the tools variable, in a separate dictinoary which key is the same as the platform name, and with specific names for each tool in turn:

cccom for the compiler, linkcom for the linker and ascom for the assembler.

For example, this is how the tools variable is defined for the i386 platform:

# Toolset data

tools[ 'i386' ] = {}

tools[ 'i386' ][ 'cccom' ] = "%s %s %s -march=i386 -mfpmath=387 -m32 -ffunction-sections -fdata-sections -fno-builtin -fno-stack-protector %s -Wall -c $SOURCE -o $TARGET" % ( toolset[ 'compile' ], opt, local_include, cdefs )

tools[ 'i386' ][ 'linkcom' ] = "%s -nostartfiles -nostdlib -march=i386 -mfpmath=387 -m32 -T %s -Wl,--gc-sections -Wl,-e,start -Wl,--allow-multiple-definition -o $TARGET $SOURCES -lc -lgcc -lm %s" % ( toolset[ 'compile' ], ldscript, local_libs )

tools[ 'i386' ][ 'ascom' ] = "%s -felf $SOURCE" % toolset[ 'asm' ]

Note how the definition of tools uses the definition of toolset, a dictionary with the names of the tools in the current toolchain. This

is also part of the eLua build system and is documented here.

- to get the name of a programmning function which receives the name of the eLua executable file (the result of the build step) and

produces a file suitable for programming on the corresponding hardware platform. The name of this function should also be set in the tools

dictionary, as shown below (example taken from the str7 platform):

# Programming function for STR7

def progfunc_str7( target, source, env ):

outname = output + ".elf"

os.system( "%s %s" % ( toolset[ 'size' ], outname ) )

print "Generating binary image..."

os.system( "%s -O binary %s %s.bin" % ( toolset[ 'bin' ], outname, output ) )

tools[ 'str7' ][ 'progfunc' ] = progfunc_str7

Note, once again, how this function uses the same toolset variable mentioned in the previous paragraph.

- stacks.h: by convention, the stack(s) size(s) used in the system are declared in this file. An example taken from the at91sam7x platform is given below:

#define STACK_SIZE_USR 2048

#define STACK_SIZE_IRQ 64

#define STACK_SIZE_TOTAL ( STACK_SIZE_USR + STACK_SIZE_IRQ )

- platform.c: by convention, the platform interface is implemented in this file. It also contains the platform-specific

initialization function (platform_init, see the description of the eLua boot process for details).

- platform_conf.h: this is the platform configuration file, used to give information about both the platform itself and the build configuration for the

platform. This is what you can set inside platform_conf.h:

- the list of components that will be part of the build (see building eLua for details).

- the list of modules that will be part of the build (see building eLua and LTR configuration

for details.

- the static configuration data (see building eLua for details).

- the number of peripherals on your CPU. See an example below (taken from lm3s) that also shows how to differentiate between different CPUs that belong to the same

platform; the FORxxxx macros are defined in conf.py):

- specific peripheral configuration: this includes (but it not limited to) enabling buffering on UART, enabling and setting up virtual timers, setting PIO configuration and so on.

All these parameters are described in detail in the platform interface section.

- memory configuration: describes the regions of free RAM in the system, which will be later used by the standard system allocator (malloc/realloc/free). Two macros

(MEM_START_ADDRESS and MEM_END_ADDRESS) define two arrays with the beginning and the end of all the free RAM memory in the system. If your board has external RAM memory, you

should define it here. If not, you can only use the internal memory, and you'll generally need to use the linker-defined symbol end to find out where your free memory starts. Following

is an example from the ATEVK1100 (AVR32) board that has both on-chip and external RAM:

// Allocator data: define your free memory zones here in two arrays

// (start address and end address)

#define MEM_START_ADDRESS { ( void* )end, ( void* )SDRAM }

#define MEM_END_ADDRESS { ( void* )( 0x10000 - STACK_SIZE_TOTAL - 1 ), ( void* )( SDRAM + SDRAM_SIZE - 1 ) }

If you want to take a look at a real life example of a platform_conf.h file, see for example src/platform/lm3s/platform_conf.h.

Besides the required files, the most common scenario is to include other platform specific files in your port:

- a "startup sequence", generally written in assembler, that does very low level

intialization, sets the stack pointer, zeroes the BSS section, copies ROM to

RAM for the DATA section, and then jumps to main.

- a linker command file.

- the CPU support package generally comes from the CPU manufacturer, and includes code

for accessing peripherals, configuring the core, setting up interrupts and so on.

eLua boot process

This is what happens when you power up your eLua board:

- the platform initialization code is executed. This is the code that does very low level platform setup (if needed), copies ROM to RAM, zeroes out

the BSS section, sets up the stack pointer and jumps to main.

- the first thing main does is call the platform specific initialization function (platform_init). platform_init must fully

initialize the platform and return a result to main, that can be either PLATFORM_OK if the initialization succeded or PLATFORM_ERR

otherwise. If PLATFORM_ERR is returned, main blocks immediately in an infinite loop.

- main then initializes the rest of the system: the ROM file system, XMODEM, and term.

- if /rom/autorun.lua (which is a file called autorun.lua in the ROM file system) is found, it is

executed. If it returns after execution, or if it isn't found, the boot process continues with the next step.

- if the shell was compiled in the image, it is started, otherwise a standard Lua interpreter is started.